A gallery of recent pet portraits I have made, paintings, sketches...inspiration....this is my non-private diary. Take a look!

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

Thursday, December 10, 2009

Sunday, November 22, 2009

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Monday, November 9, 2009

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Thursday, October 29, 2009

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Monday, October 26, 2009

Friday, October 23, 2009

Monday, October 19, 2009

Sunday, October 18, 2009

Friday, October 16, 2009

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

Sunday, October 4, 2009

Friday, October 2, 2009

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Sunday, September 27, 2009

want want

adorable and or beautiful things....because today I am taking a break from adorable and beautiful people.

want want a short vintage jacket. And a cup of strong coffee.

want want a short vintage jacket. And a cup of strong coffee.

Saturday, September 26, 2009

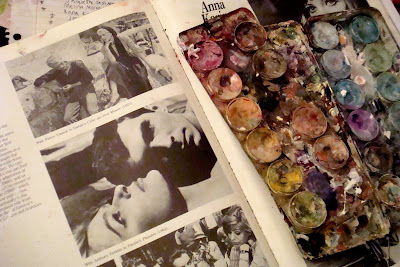

Brooklyn-stoop sale-epiphany-serotonin?

Stoop sales will probably stop for a while, now that September is ending, and cold weather is creeping up. I passed a few great ones on the walk back from the gym. One in particular-with a certain out of print book that was propped up by a pair of salt and pepper shakers. I <3 this weekend already...

The illustrator of this book was the love of my mom's life in 1958. It is a treasure to me-even though it only cost me a dollar. (My enthusiasm was downplayed and under appreciated by the guy on the stoop who was selling his unwanted clutter)

Anyway...this set off some kind of romantic chemical in my brain. For the rest of the walk home, I daydreamed about really becoming a writer. I love daydreams like that-But now I need a nap.

The illustrator of this book was the love of my mom's life in 1958. It is a treasure to me-even though it only cost me a dollar. (My enthusiasm was downplayed and under appreciated by the guy on the stoop who was selling his unwanted clutter)

Anyway...this set off some kind of romantic chemical in my brain. For the rest of the walk home, I daydreamed about really becoming a writer. I love daydreams like that-But now I need a nap.

Friday, September 25, 2009

Monday, September 21, 2009

another one for mom on her birthday

I wrote this ages ago....

Second Hand Heroes

Second Hand Tramp is a vintage clothing shop downtown. You can go there to daydream about flamboyance and masquerades. It’s a store where you can dress up like a doll, in classic relics of the glamour years. You can rummage through the flapper aisles and find a slinky feathered boa. A five point rhinestoned tiara. A pale creme slip dress with a plunging sweetheart neckline. But everything is too expensive for you take home.

Pomade Johnny works in the 1940’s section, whistling a kiss is just a kiss. You show him everything you want but can’t have. In strapless mint chiffon, he says you’re breaking all the rules. You should try it with some fishnets, (baby)< to be fancy.

You are here-in a costume shop and a playground. Those are words your mother might have said, while flipping through dresses on a 1950’s rack. The undesired left-behinds from an overdosed blonde with vintage curves.

Here, you can feel inspired to write love poems for boyfriends who you have misplaced. Poems that you had chosen not to finish. You left those lovers dreary and ambiguous.

Scotty is your closest friend. He found you at the end of spring, one day, when your face was a smear of teardrops and the rain. He took you home when you said you were a stray. A soggy stray, he must have thought. You stayed for soup. You stayed all spring.

Slow afternoons in dim blue light, on a flannel sofa with no social calls. Then the quietness made memories and loneliness noisy in your head.

Scotty is a New York anti social wreck. His apartment is full of books- long books that he starts but can not finish. He never reads fiction. And he never lies to you. He never hurts you. He always wants you around. But there is something wrong. There is something about comfort that has always made you nervous. Perhaps because you swear you've seen him lie to other people. Perhaps because

he has never learned to understand your point.

Last night you made banana splits. You told Scotty some stories about Shu-Shu, your old orange cat. He was your closest friend when you were a little girl, before you started getting boyfriends.

That honey natured, handsome brute. You loved every whisker. El magnifico. He was Zorro, when you strapped your mother’s nightshades to his ears. He wore a paper top hat, every Christmas. You've got all those Holiday baby photos, like the one of you in your mother’s arms. You put that one in a frame; She’s holding you mid giggle. The paper hat is on the tip of Shu-Shu is between you, pressed like sticking paper to your mothers Christmas sweater. Your father took that picture. A record of what your family looked like before everything changed.

Shu-Shu had piggy fat. You called him pig. Love was kissing your pig. That’s what you told Scotty last night. His nose was in a book.

You moved closer on the sofa so that the book jacket brushed against your brow. You lost an eyelash in its spine. Then you told Scotty you were having a fantasy.

“Tomorrow morning, a rail road train. Don’t bring bills to pay. Don’t bring the paper, don’t even bring the crossword. No books, and no magazines will be allowed.

Only holding hands and legs. And thighs.

We will pass run down houses. Clothing lines with hanging bed sheets and small town people’s underwear. We’ll get off to have pie. And then if inclined wine. And then if more inclined a bedroom somewhere to ravage each other meaningful. Then a bath and eggs sent to the room. The night will come, midnight blue with two pale stars. We will re-train. When we get back we’ll be emotionally evolved. We will be so charged with Technicolor visions and panoramic memories. We’ll need to walk around in shady eyeglasses so our iris and our corneas can readjust.”

It was a flashy fantasy. It came out fast, and in excited run ons.

“Was he a nice cat? Like a dog?” Scotty asked. And swished the eyelash off his book.

“He wasn’t like a dog Scotty. He was like a cat.”

Scotty picked up his reading again. He stayed breathing into his book. Not on you. Mae West was on t.v. Whispering, want me. Want me. And you ate all of Scotty's dessert.

Maybe if you had loved your man last night, you could have writen him a poem this afternoon. Maybe now you could write a poem to fix everything that has going wrong.

You start one in your head. About a boy in glasses who writes non fiction. He hates all fiction except for Bob Dylan. And he romances you in black unlustrous swoops.

But...you are distracted by a red velvet clutch purse. It looks like a valentine. It was made for you.

Pomade Johnny smiles as you press ruffles to your cheek. He is Southern, like a poster boy in a retro ad for Pepsi Cola. Full lips to kiss a girl passionate, on the hood of a whisper blue Trans-am, weeping cowboy music. All in denim, with a tattoo on his left arm bicep. A heart torn in half. One side says I Never Cried the other side says Cherry Pie. You feel he has a tickle for you. You make eyes at Johnny, then shyly turn away to look at hats.

As a child your mother was very sick. She lay in bed for days. You knew she got lonely. You would tap dance for her, and hula-hoop with Piggy.

Knock Knock,

Who’s there?

Shu-Shu Piggy’s underwear!

Settle Down, she’d say. So you’d lie with her and pretend to sleep. Her hands were cold, and she always lay with a pillow between her knees. Sometimes you could make your mommy smile, but you could never make her well.

Johnny comes behind you and smothers you in black feathers.

“Shanghai Lily,” he suggests.

“Trouble is my business,” you return.

He starts you up a dressing room of the costumes he’s watched you get dreamy over. First you try a twenties tutu dress that’s waisted at the hip. You’ve got flappers rash. Like a Kansas City candy girl, who packed her bags to be a Hollywood jazz baby.

Pomade Johnny turns your stockings down. He sings about Charlestons, gin fizzies and a manhandled coquette. Ziegfeld’s folly. You twirl fake pearls, and go back to your dressing room, walking on your toes.

In a dark velvet smoking jacket with padded shoulders, you look on your game. You are a broad. A postwar handsome dame with guts. The kind who wears pants and never turns her men off. The kind with over penciled scarlet lips to reaffirm she’s got a big mouth. The jacket comes with an ivory ermine muff.

Johnny brings you after dinner gloves in dove grey, and a cloche hat lined with pearls. It’s too small. It triggers hat nostalgia. Sad hat mishaps. You begin hating nostalgia and Tramps.

When you were thirteen, you pinned shoulder bows to your mother’s hospital gown. When cancer drugs made her lose her hair, you designed a delicate bonnet trimmed with crepe paper. Yellow roses. Hats became your bag. You did a summer line. Her favorite was made of navy straw and glue gunned red felt ladybugs.

The last hat you made for your mother was a style you had copied from a movie with Claudette Colbert. You were too fast and imprecise. It was a bad hat, because it didn’t cover enough head. You cried about that hat. You cried so much on your mother, that her pajamas became soaked.

When you grew older, your mother told you to keep making new friends. She told you she was sorry she could never make you laugh.

In the mirror at Second Hand Tramp, you are crying into the costumes. And you don’t want Pomade Johnny to catch you this way. You miss her. You try to make friends easy, but you can only attract downers. You get close to a guy like Scotty, and you feel that it is your calling to lighten him up. But he’ll hate cats and hula-hoops and candy.

You change back to blue jeans, and try to sneak out of the shop unnoticed. You walk into another rainy day, and then suddenly you are being umbrellaed.

Pomade Johnny puts you in a cab. He has snuck out the valentine clutch purse, and he tucks it in your lap.

“You might have said goodbye,” he says.

“ Next time,” you say back.

The taxi takes you home, and you hold onto the purse tightly.

Second Hand Heroes

Second Hand Tramp is a vintage clothing shop downtown. You can go there to daydream about flamboyance and masquerades. It’s a store where you can dress up like a doll, in classic relics of the glamour years. You can rummage through the flapper aisles and find a slinky feathered boa. A five point rhinestoned tiara. A pale creme slip dress with a plunging sweetheart neckline. But everything is too expensive for you take home.

Pomade Johnny works in the 1940’s section, whistling a kiss is just a kiss. You show him everything you want but can’t have. In strapless mint chiffon, he says you’re breaking all the rules. You should try it with some fishnets, (baby)< to be fancy.

You are here-in a costume shop and a playground. Those are words your mother might have said, while flipping through dresses on a 1950’s rack. The undesired left-behinds from an overdosed blonde with vintage curves.

Here, you can feel inspired to write love poems for boyfriends who you have misplaced. Poems that you had chosen not to finish. You left those lovers dreary and ambiguous.

Scotty is your closest friend. He found you at the end of spring, one day, when your face was a smear of teardrops and the rain. He took you home when you said you were a stray. A soggy stray, he must have thought. You stayed for soup. You stayed all spring.

Slow afternoons in dim blue light, on a flannel sofa with no social calls. Then the quietness made memories and loneliness noisy in your head.

Scotty is a New York anti social wreck. His apartment is full of books- long books that he starts but can not finish. He never reads fiction. And he never lies to you. He never hurts you. He always wants you around. But there is something wrong. There is something about comfort that has always made you nervous. Perhaps because you swear you've seen him lie to other people. Perhaps because

he has never learned to understand your point.

Last night you made banana splits. You told Scotty some stories about Shu-Shu, your old orange cat. He was your closest friend when you were a little girl, before you started getting boyfriends.

That honey natured, handsome brute. You loved every whisker. El magnifico. He was Zorro, when you strapped your mother’s nightshades to his ears. He wore a paper top hat, every Christmas. You've got all those Holiday baby photos, like the one of you in your mother’s arms. You put that one in a frame; She’s holding you mid giggle. The paper hat is on the tip of Shu-Shu is between you, pressed like sticking paper to your mothers Christmas sweater. Your father took that picture. A record of what your family looked like before everything changed.

Shu-Shu had piggy fat. You called him pig. Love was kissing your pig. That’s what you told Scotty last night. His nose was in a book.

You moved closer on the sofa so that the book jacket brushed against your brow. You lost an eyelash in its spine. Then you told Scotty you were having a fantasy.

“Tomorrow morning, a rail road train. Don’t bring bills to pay. Don’t bring the paper, don’t even bring the crossword. No books, and no magazines will be allowed.

Only holding hands and legs. And thighs.

We will pass run down houses. Clothing lines with hanging bed sheets and small town people’s underwear. We’ll get off to have pie. And then if inclined wine. And then if more inclined a bedroom somewhere to ravage each other meaningful. Then a bath and eggs sent to the room. The night will come, midnight blue with two pale stars. We will re-train. When we get back we’ll be emotionally evolved. We will be so charged with Technicolor visions and panoramic memories. We’ll need to walk around in shady eyeglasses so our iris and our corneas can readjust.”

It was a flashy fantasy. It came out fast, and in excited run ons.

“Was he a nice cat? Like a dog?” Scotty asked. And swished the eyelash off his book.

“He wasn’t like a dog Scotty. He was like a cat.”

Scotty picked up his reading again. He stayed breathing into his book. Not on you. Mae West was on t.v. Whispering, want me. Want me. And you ate all of Scotty's dessert.

Maybe if you had loved your man last night, you could have writen him a poem this afternoon. Maybe now you could write a poem to fix everything that has going wrong.

You start one in your head. About a boy in glasses who writes non fiction. He hates all fiction except for Bob Dylan. And he romances you in black unlustrous swoops.

But...you are distracted by a red velvet clutch purse. It looks like a valentine. It was made for you.

Pomade Johnny smiles as you press ruffles to your cheek. He is Southern, like a poster boy in a retro ad for Pepsi Cola. Full lips to kiss a girl passionate, on the hood of a whisper blue Trans-am, weeping cowboy music. All in denim, with a tattoo on his left arm bicep. A heart torn in half. One side says I Never Cried the other side says Cherry Pie. You feel he has a tickle for you. You make eyes at Johnny, then shyly turn away to look at hats.

As a child your mother was very sick. She lay in bed for days. You knew she got lonely. You would tap dance for her, and hula-hoop with Piggy.

Knock Knock,

Who’s there?

Shu-Shu Piggy’s underwear!

Settle Down, she’d say. So you’d lie with her and pretend to sleep. Her hands were cold, and she always lay with a pillow between her knees. Sometimes you could make your mommy smile, but you could never make her well.

Johnny comes behind you and smothers you in black feathers.

“Shanghai Lily,” he suggests.

“Trouble is my business,” you return.

He starts you up a dressing room of the costumes he’s watched you get dreamy over. First you try a twenties tutu dress that’s waisted at the hip. You’ve got flappers rash. Like a Kansas City candy girl, who packed her bags to be a Hollywood jazz baby.

Pomade Johnny turns your stockings down. He sings about Charlestons, gin fizzies and a manhandled coquette. Ziegfeld’s folly. You twirl fake pearls, and go back to your dressing room, walking on your toes.

In a dark velvet smoking jacket with padded shoulders, you look on your game. You are a broad. A postwar handsome dame with guts. The kind who wears pants and never turns her men off. The kind with over penciled scarlet lips to reaffirm she’s got a big mouth. The jacket comes with an ivory ermine muff.

Johnny brings you after dinner gloves in dove grey, and a cloche hat lined with pearls. It’s too small. It triggers hat nostalgia. Sad hat mishaps. You begin hating nostalgia and Tramps.

When you were thirteen, you pinned shoulder bows to your mother’s hospital gown. When cancer drugs made her lose her hair, you designed a delicate bonnet trimmed with crepe paper. Yellow roses. Hats became your bag. You did a summer line. Her favorite was made of navy straw and glue gunned red felt ladybugs.

The last hat you made for your mother was a style you had copied from a movie with Claudette Colbert. You were too fast and imprecise. It was a bad hat, because it didn’t cover enough head. You cried about that hat. You cried so much on your mother, that her pajamas became soaked.

When you grew older, your mother told you to keep making new friends. She told you she was sorry she could never make you laugh.

In the mirror at Second Hand Tramp, you are crying into the costumes. And you don’t want Pomade Johnny to catch you this way. You miss her. You try to make friends easy, but you can only attract downers. You get close to a guy like Scotty, and you feel that it is your calling to lighten him up. But he’ll hate cats and hula-hoops and candy.

You change back to blue jeans, and try to sneak out of the shop unnoticed. You walk into another rainy day, and then suddenly you are being umbrellaed.

Pomade Johnny puts you in a cab. He has snuck out the valentine clutch purse, and he tucks it in your lap.

“You might have said goodbye,” he says.

“ Next time,” you say back.

The taxi takes you home, and you hold onto the purse tightly.

how i used to write about my mom

One Way

We are not made of sugar. That’s how my mother would say do not make fusses about walking in the rain. I was seven. I told her that the raindrops made me need to pee. Settle down, she’d say, as we drove down the hill to buy some groceries.

Belted safely in her chiclets-yellow Oldsmobile Omega, we drove past Angelinos jogging by the coral trees.... The rain was keeping them cool, mom said. Her radio played Good-day-Sunshine songs.

When we got there, I felt shy. I held a corner of her handbag, not her hand. I was watching people’s sneakers when she told me, pick a soup. The market floor was sticky from the rain tread in. Its green Palmolive tile felt like dirty glass.

Let’s not make a career out of shopping at the country mart, she said. That’s how my mother told me my decisions took too long.

With her long swan neck and ballerina legs, she seemed taller than the other mothers. Her denim jeans fit like she’d been dipped into them. Her high healed zipper boots made a tap, tap, click, click, and click. She also wore a smoking jacket, black cherry colored, with a sash made out of faux bunny fur. It came from New York City with a label that said “!!!!”

She was hard to understand. Her presence at the market was noticeably non-suburban. She had kitten eyes, lined with blue-black pencil. Her eye color was pale, pale blue. Her hair was silky black; as shiny as Chinese teacups. She usually pulled it into a bun. She wore it down that day. More people would look at her when my mother’s hair was down.

We liked the men who did their work in aprons. The Grocers shared our sense of time and tempo. From aisle to aisle, they seemed to glide. We’d smile or say hello as we walked by them. Spraying fruits and veggies they would say, the mangoes are good today. The apricots are almost ripe. But the grocers didn't wave or whistle to the other women pushing shopping carts. These were our neighbors, who were never in a hurry. We bumped into them sometimes. It would slow my mother down.....

................

We could share a great big secret, just by smiling. My mother taught me how to smile in a way that said “!!!! At the cashier, Handsome Dr. Blue stopped by to say hello.

“I recognized you from behind,” he told my mother. He didn’t notice me. Or else I pretended I wasn’t there.

....................

My mother made heirlooms that afternoon, after we drank soup. She said she was sorry that we didn’t have any. We sat at the kitchen table. She was quilting throw cushions, patterned with scenes from our back garden. The daisies and the mandarin trees. I made my own homage. Muddy watercolors of what I saw through rain smeared windowpanes.

“Stupid, stupid, bad,” I said about those watercolors. And I told her that Art hurt my feelings.

Nothing garish grew in that garden. The Eucalyptus was a dusty, mild, faded green. The lemon trees made dull off yellow fruit, never ripe for juice. And then there were two birds of paradise, which stood out extreme. Their colors seemed to be screaming mad. Red vermilion, and orange. My mother liked it that way.

I envied the symmetry in the patterned shapes my mother made. Perfect flowers not even traced or measured. My flowers were lousy. My paintings had design flaws.

“There’s no such thing as a perfect circle,” my mother told me. In Marvy Markers I drew my mother gardening wild flowers. Flowers the color of stained glass.

“Come here” she said. She let me sit on her lap, despite my design flaws.

“I will always be your mommy. You can always talk to

me. But, don’t have hurt feelings if the conversation is only one way.”

Most of that year was quiet. She was sick. Then bed ridden in her white room. Cold and hot. “That’s nice,” she said, when I held a wet cloth on her forehead. She didn’t have the strength to quilt our heirlooms.

.................

I think about those perfect circles she made. I rarely see them anymore. Still, sometimes I do talk to my mother. To one of her handbags or to a fresh bouquet of flowers in her vase. I try to balance sad and funny.

After a rough day I’ll complain to her handbag about the subway. I gave my seat to a teenage mother who looked knocked up again. She yanked her daughter up the stairs too fast when they got off. Her daughter smiled at me. She had daisy barrettes with; I love Jesus in the petals.

I tell my mother’s flower vase about the homeless lady who lives down my block. “You’re ugly!” she says, each time I walk past. I go out of my way to avoid going by her.

I miss mom a lot today. I'm all grown up in that jacket, of ill repute. On me it hangs mid thigh. I’m at the modern art museum with a pink satin notebook tucked under my arm. This notebook was a gift from Sam. “Don’t write in between the lines,” he wrote inside.

..............

There is a small gallery in the museum, where I like to get dreamy. I go here a lot. Loud non-art lovers sometimes block my view. “Looks like New York street pee,” some one says. I know to never look these people in the eye. My mother would have stretched her legs and smile slightly without opening her mouth. The look is perfect.

I see her face in a painting from the 1920’s. French haircut. Fair skin. Red lips, long neck. Kitten eyes the color of pale blue water.

When I close my eyes I shut out distraction. And then I see her in a Degas pose. She’s lounging on a white Eames chair with her legs out on the ottoman.

That coat looks great on you, she says. Then why make troubles with your man?

See what you’ve done? There’s nobody left who is unflawed like you..............

We are not made of sugar. That’s how my mother would say do not make fusses about walking in the rain. I was seven. I told her that the raindrops made me need to pee. Settle down, she’d say, as we drove down the hill to buy some groceries.

Belted safely in her chiclets-yellow Oldsmobile Omega, we drove past Angelinos jogging by the coral trees.... The rain was keeping them cool, mom said. Her radio played Good-day-Sunshine songs.

When we got there, I felt shy. I held a corner of her handbag, not her hand. I was watching people’s sneakers when she told me, pick a soup. The market floor was sticky from the rain tread in. Its green Palmolive tile felt like dirty glass.

Let’s not make a career out of shopping at the country mart, she said. That’s how my mother told me my decisions took too long.

With her long swan neck and ballerina legs, she seemed taller than the other mothers. Her denim jeans fit like she’d been dipped into them. Her high healed zipper boots made a tap, tap, click, click, and click. She also wore a smoking jacket, black cherry colored, with a sash made out of faux bunny fur. It came from New York City with a label that said “!!!!”

She was hard to understand. Her presence at the market was noticeably non-suburban. She had kitten eyes, lined with blue-black pencil. Her eye color was pale, pale blue. Her hair was silky black; as shiny as Chinese teacups. She usually pulled it into a bun. She wore it down that day. More people would look at her when my mother’s hair was down.

We liked the men who did their work in aprons. The Grocers shared our sense of time and tempo. From aisle to aisle, they seemed to glide. We’d smile or say hello as we walked by them. Spraying fruits and veggies they would say, the mangoes are good today. The apricots are almost ripe. But the grocers didn't wave or whistle to the other women pushing shopping carts. These were our neighbors, who were never in a hurry. We bumped into them sometimes. It would slow my mother down.....

................

We could share a great big secret, just by smiling. My mother taught me how to smile in a way that said “!!!! At the cashier, Handsome Dr. Blue stopped by to say hello.

“I recognized you from behind,” he told my mother. He didn’t notice me. Or else I pretended I wasn’t there.

....................

My mother made heirlooms that afternoon, after we drank soup. She said she was sorry that we didn’t have any. We sat at the kitchen table. She was quilting throw cushions, patterned with scenes from our back garden. The daisies and the mandarin trees. I made my own homage. Muddy watercolors of what I saw through rain smeared windowpanes.

“Stupid, stupid, bad,” I said about those watercolors. And I told her that Art hurt my feelings.

Nothing garish grew in that garden. The Eucalyptus was a dusty, mild, faded green. The lemon trees made dull off yellow fruit, never ripe for juice. And then there were two birds of paradise, which stood out extreme. Their colors seemed to be screaming mad. Red vermilion, and orange. My mother liked it that way.

I envied the symmetry in the patterned shapes my mother made. Perfect flowers not even traced or measured. My flowers were lousy. My paintings had design flaws.

“There’s no such thing as a perfect circle,” my mother told me. In Marvy Markers I drew my mother gardening wild flowers. Flowers the color of stained glass.

“Come here” she said. She let me sit on her lap, despite my design flaws.

“I will always be your mommy. You can always talk to

me. But, don’t have hurt feelings if the conversation is only one way.”

Most of that year was quiet. She was sick. Then bed ridden in her white room. Cold and hot. “That’s nice,” she said, when I held a wet cloth on her forehead. She didn’t have the strength to quilt our heirlooms.

.................

I think about those perfect circles she made. I rarely see them anymore. Still, sometimes I do talk to my mother. To one of her handbags or to a fresh bouquet of flowers in her vase. I try to balance sad and funny.

After a rough day I’ll complain to her handbag about the subway. I gave my seat to a teenage mother who looked knocked up again. She yanked her daughter up the stairs too fast when they got off. Her daughter smiled at me. She had daisy barrettes with; I love Jesus in the petals.

I tell my mother’s flower vase about the homeless lady who lives down my block. “You’re ugly!” she says, each time I walk past. I go out of my way to avoid going by her.

I miss mom a lot today. I'm all grown up in that jacket, of ill repute. On me it hangs mid thigh. I’m at the modern art museum with a pink satin notebook tucked under my arm. This notebook was a gift from Sam. “Don’t write in between the lines,” he wrote inside.

..............

There is a small gallery in the museum, where I like to get dreamy. I go here a lot. Loud non-art lovers sometimes block my view. “Looks like New York street pee,” some one says. I know to never look these people in the eye. My mother would have stretched her legs and smile slightly without opening her mouth. The look is perfect.

I see her face in a painting from the 1920’s. French haircut. Fair skin. Red lips, long neck. Kitten eyes the color of pale blue water.

When I close my eyes I shut out distraction. And then I see her in a Degas pose. She’s lounging on a white Eames chair with her legs out on the ottoman.

That coat looks great on you, she says. Then why make troubles with your man?

See what you’ve done? There’s nobody left who is unflawed like you..............

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Thursday, September 17, 2009

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Monday, September 14, 2009

Saturday, September 12, 2009

Friday, September 11, 2009

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)